I’ve been trying to get back to writing recently, but I’ve been spending most of my cognitive capacity on a lecture I’ve been putting together for the most recent class of the wind power master’s program in Visby, Sweden. It ended up being mostly a cultural history of the United States to provide a bit of context for a bunch of Asians, most of whom have never been to the US.

I figured this might be relevant to others as well, and with how much energy I put into it, I feel like this is the best place I have to share. If you have any interest at all in the state of renewable energy in the US, you might find this relevant. If not, the next twenty minutes of your life could be better spent. but if your alternative is to go scroll the twitbook, then do yourself a favor and focus on anything else, really… anything.

Introduction

Even though most of you will not be working the US anytime soon (if ever; there are only 85,000 visas available, and they’re extremely competitive), understanding the US industry can be a valuable exercise. There are some key peculiarities of the US wind industry that can be instructive when comparing development curves around the world.

You’ve been learning a lot about how wind energy works in Europe (and there are a lot of similarities that have been exported to Asia and Africa), but the US is a different beast. In Europe, the government has often picked out areas of special interest for wind energy development, and developers are mostly competing for those spots. It is the exact opposite in the US. Developers in the US go find the land that would be good for a wind farm and then convince the local, state, or federal government (rarely all three) that they should be allowed to build (If you’re not familiar with the US federalist system, check out this explanation: https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/state-local-government/).

In Europe, the typical forms of subsidies are contract for difference, feed-in tariff, green certificate, etc. Especially in the offshore sector, developers win subsidies in auctions with the government taking the proactive step of procuring renewable energy. As far as I know, no such thing exists in the US. The only support scheme from Washington was the Production Tax Credit (PTC), which we will cover in detail.

In Europe, the grid is typically a national entity directly subject to the will of the government. The US grid is a patchwork of thousands of investor-owned and municipal utility companies tightly regulated by states, coordinated by regional TSO-like companies, which are in turn overseen by a federal commission.

These are just a few of the key differences between the US and Europe. I’m sure there are many more, but these are the ones most obvious to me based on my experiences. Over the course of this hour, I aim to provide a handful of resources for the curious among you who want to learn more about American wind power and to highlight some aspects of the wind energy culture that may not be obvious to you.

Like how learning a foreign language helps you understand the structure of your own language, this exploration into the US wind industry ought to help you identify some of the important aspects of the industry you are about to enter.

This lecture comes in four parts:

1. A brief history of the United States

2. The American wind industry in context

3. The current state of the industry

4. The future of the industry

A brief history of the United States

In order to understand the development of American wind power and the potential directions it might take, it is essential to understand America. The development curve of wind power capacity looks very similar to the curve around the world, and purely statistical analysis would lead one to think that certain paths are more likely than they really are in a nation that is fundamentally different from much of the rest of the world.

Born of Rebellion

The differences go deep, and they start even before the beginning. The first colonies were mostly founded as either havens to escape religious persecution by religious European governments (e.g. Maryland, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania) or as profit-seeking ventures (e.g. Virginia, New Hampshire, Delaware, the Carolinas). By the middle of the eighteenth century, it is true that most colonists saw themselves as “British”, but most had been born in the colonies, which were more-or-less self-governed and organized. For decades, the colonies had been de facto autonomous in a period known as salutary neglect.

When the British Crown, in 1763, started enforcing laws that had been ignored for a century, resentment toward the distant master started to grow. Colonists who had found on the North American front of the Seven Years’ War (known over here as the French and Indian War) wanted to settle in the newly won lands, but the Crown wanted to use them to pay their enormous war debts and forbade settlement. Over the ensuing decade, tightening control from Westminster grew sentiment to the point that a group of legislators and community leaders gathered in Pennsylvania to draft a declaration of independence.

The foundational document, still read by American school children today, states in the second paragraph, “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable [sic] Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” It goes on to state that a government is instituted to protect these rights, and when it fails to do so, “it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it….” These sentiments have been taught to Americans for generations, and many of us have memorized the above quotation. Such values have become prevalent in European society in the past several decades, but in few places do such ideals of independence, equity, and autonomy run so deeply.

After the colonies won their independence, they did not initially form a unified nation. The first governing document, The Articles of Confederation, described a loose cooperation between states that gave almost no power to a national government and was far weaker than even the original European Union. It quickly became apparent to American leaders that a more solid union would be necessary. The United States Constitution, written in 1787, laid the groundwork for “the United States”. It is exceptionally brief, at just over 4500 words, explaining the very limited powers that the federal government has.

Before it is even ratified by the states, a swift and unanimous call for a “Bill of Rights” results in the first 10 amendments, all of which impose sharp limits on federal power and ensure a long list of rights. Among these are the right to form a militia and to keep the deadly weapons necessary for such a force. There is much controversy about the details of that amendment, but it is naive not to accept that the second amendment was to ensure that citizens would have the means to lead a revolution against a government that became too tyrannical. This has been forgotten by many urbanites and coastal elites, but the vast middle of the country (where the best wind is) knows this well.

The prevalence of gun ownership in the United States (double the next highest region and triple the first European country) is often unsettling to Europeans who may never have seen a gun in their lives. The second amendment is one reason for this, but another reason is that most American families still have someone who remembers a time or currently lives in an area when law enforcement was or is useless in protecting one’s family and property.

Self-selected for self-reliance

In the East, the latter half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century, over a quarter of a million immigrants were coming to the country each year, coming to a climax of over 1.2 million immigrants in 1907. At any given time from 1870 to 1910, nearly 15% of the US population were foreign-born (the number dropped over the ensuing century but is now back to that level). These weren’t high-skilled college graduates from wealthy families. These were people fleeing displacement, poverty, famine, persecution, and overpopulation. They were self-starters and risk-takers. They risked everything they had on starting over in the New World.

Those who succeeded did so with very little help from governments. The few institutions that cared for the poor were often “deliberately harsh so that only the truly desperate would apply.” Personal responsibility was a part of the American psyche, and those who experienced the true meaning of that phrase are our great grandparents who passed those lessons on to us. They came to define what an “American” is. Most white Americans can trace at least one family line to this period. Three of my four grandparents were raised by immigrant parents who came from Poland and Italy in the late nineteenth century.

In the West, life was even harder. The United States doubled in size at the turn of the nineteenth century with the Louisiana Purchase and then stole another half a million square miles from Mexico in 1848. This land was mostly empty, occupied by some Mexicans and by the remaining American Indian tribes, whose numbers had not recovered from the microbial holocaust inflicted upon them when Europeans brought centuries of plagues to the New World all at once. During and after the Civil War, the government gave away hundreds of millions of acres of land to settlers and private companies who would tame this vast wild land. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave away 270 million acres, and railroad grants gave away 130 million acres to connect the country with the new steam engine. These were rough places where a bad crop meant starvation, and death was a common workplace hazard. Natural selection acted on humans the same as any other species. The strong survived; the rest did not.

Nowadays, the federal government owns about 28% of the US (including a huge chunk of Alaska). The state governments own another 9%, and most of that 37% of America is national parks, national forest, and other protected areas. The remaining 63% of land is owned by private entities. If you want to build on public lands, you need lots of permits, which may not be granted because those are often protected. If you want to build on private land, you’re going to need to pay the owner a fair price either to rent it or buy it.

The development of the West was not led by the government. They gave away land so that private enterprises could take the reins. The most successful enterprises were engaged in resource extraction. Prospectors filed in the thousands to seek gold in California and Colorado. Even though gold rushes only lasted a few years, those who ended up there weren’t about to move again, and so settled cities like San Francisco and Denver. At the time, the industrial world ran on coal, and the internal combustion engine would soon lead to oil booms in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and others. Cities like Houston, Texas and Butte, Montana were built on these. Basically, the entire economy of Wyoming relies on coal mining to this day. The extraction was done with little regard for environmental impact. The new country was so vast that any permanent damage could simply be left to let nature slowly repair it while extraction moved to another stretch of pristine landscape. The first major environmental protection laws were nearly a century away. When most people settled new lands in America, private industry was king, and the government was a distant annoyance.

The birth of the modern utility

The cities that developed from the expansion of the late nineteenth century would soon be electrified, and in a similar fashion to all other development, private industry took the lead. The massive capital investment required to connect a city to a large power plant meant that utilities built natural monopolies. Eventually, the government would reinforce these monopolies to encourage other entrepreneurs to invest in other developments instead of redundant electrical transmission systems. In exchange, these monopolies accepted heavy government oversight. Today, most utilities are overseen by a Public Utilities Commission (PUC) or similar that is part of the state government. In the late twentieth century, private organizations, known as Independent System Operators (ISOs) and Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) were created by the federal government to coordinate the utilities and are overseen by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Some states have broken up vertically integrated utilities, but some still allow utilities to own both the generating units and the transmission lines. Instead of national grids, we have private grids that are kept in check by public commissions who are either elected or appointed by an elected government.

National identity… anything but a commie

The ideals of capitalism and private ownership took hold just as the world was being swept with nationalism, and these ideas grew even more deeply into the American identity when the Soviet Union, a nation that rejected private ownership and embraced a centrally planned economy, became the great rival. The United States embraced a form of negative integration, in which we defined ourselves based on what we were not. We were not communist or socialist, and we were definitely not atheists (which until recently was the least liked demographic in the US). On top of positioning ourselves as the polar opposite of the “Ruskies”, Americans were scared. The threat of nuclear war loomed over everyone. It was (and still is) a real threat, but then it often seemed inevitable. People fled to suburbs so that they might be outside the blast radius of a bomb targeting a city, they built bomb shelters where they might wait out the nuclear holocaust above, and they prepared constantly for Soviet invasion or nuclear attack.

I’m often asked what differences I see between the US and Europe. The biggest thing I always see is fear. I can’t be sure, but I think the fact that most of our leaders grew up in the shadow of the constant threat of annihilation has a lot to do with it. The Cold War and the geography of massive open spaces define what much of America is (or at least what it claims to be). We idealize self-reliance and idolize rags-to-riches stories. We support the free market and states’ rights because there’s no way that a bunch of Washington elites could have any idea what we want or need thousands of miles away. We pray to God because we know that the government is just as likely to oppress us as protect us. We are always ready for whatever threat arises because we live in a harsh world at the mercy of a capricious God. But in that God, we trust, and we are united under His mercy and protection from the Soviets.

America, divided.

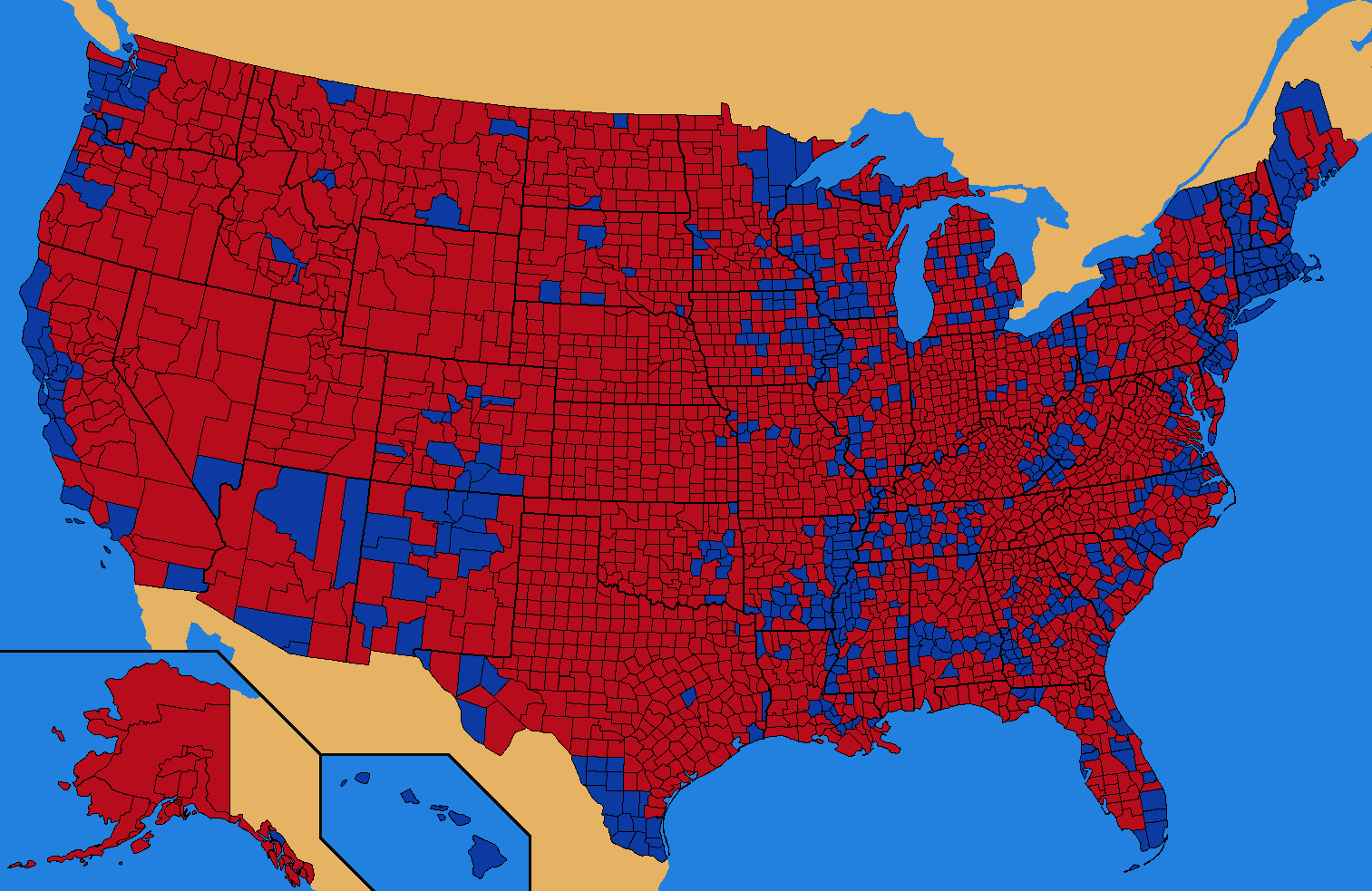

But in 1991, the Soviets ceased to exist. Decades of internal tensions began to get attention. Animosity toward an external enemy turned toward internal ones. When we lost something to unite against, we started to rearrange ourselves based on our differences. The political right wanted to focus on our exceptionalism, the things that made us American (duty, honor, country). The left wanted to focus on differences of those who had been marginalized (gays, cripples, retards, and other minorities). Left-leaning urban elites pushed for “politically correct” laws and culture, and the right recoiled at the echos of Marxist ideals of equality of outcome, departure from traditional values, and growing power of the national government. These communities that cover the vast interior. This is clear in the 2000 presidential election results. This map shows county results. Red for Republican (George W. Bush, former Texas Governor) and blue for Democrat (Al Gore, former Vice President under Bill Clinton).

The overwhelming majority of those red counties in the middle of the country are sparsely populated, so the Republicans didn’t dominate the election; it was in fact nearly a perfect tie. What other kind of area is sparsely populated? Ideally one on a large, flat plain? Wind farms.

Only a few months after George W. Bush took office, the US experienced perhaps its most transformative day since the attack on Pearl Harbor: the terrorist attacks of September 11th. It would be folly to say that any aspect of American life was not affected by 9/11. While foreign policy sent men and women overseas to fight, domestic policy looked inward, reinvigorating the desire to be energy independent.

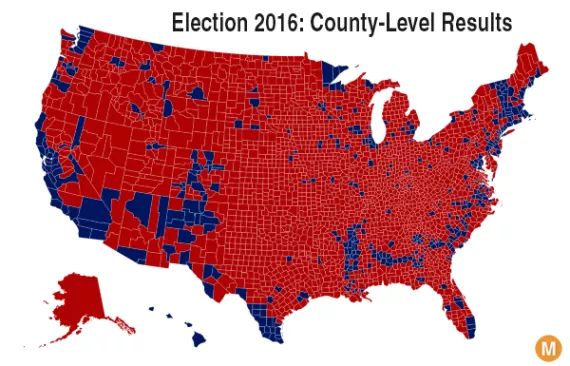

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan dragged on for five, ten, and then eighteen years in Afghanistan, Americans grew more divided. Social media has allowed us to silo ourselves even more than we had. Greater stakes for political involvement and more liberties around political speech have allowed greater influence on legislation of corporate interests. All the while, urban elites continue to get richer while the working class of the vast middle of the country (and everywhere really) has fallen behind. As the political left moves more toward socialism and making sure everyone has a label to identify themselves, the right tries to hold onto the pride of independence that their forebears fought for and instilled in them. As a result, the country continues to divide itself along political lines. In my own humble opinion, the Republicans could have run a cardboard box as their candidate, and this map would look basically the same:

http://metrocosm.com/election-2016-map-3d/

The American wind industry in context

To discuss wind energy in America is to discuss energy as a whole. For decades, the United States has been striving to become energy independent. While we have more coal than we know what to do with, we’ve needed large imports of oil and natural gas to run our extremely energy-hungry society.

The early days

Like in Europe, the oil embargo of 1973 hit the US hard. Up to that point, Americans had seen their fuels as effectively limitless. When the supply was cut off, we decided that we needed to be able to control the supply ourselves. The National Energy Act of 1978 incentivized basically every way to avoid using oil. That included increasing coal production and setting a cap on the price of natural gas. It also included provisions for expanding the use of rooftop solar and tax credits for expenditures on renewable energy infrastructure, including wind turbines. As a result, the US saw its first “wind rush” over the next few years. The world’s first wind farm (if you could call it that) went up at Crotched Mountain in New Hampshire in 1980, funded entirely by private funds with the hope of attracting major investment. However, the 20 30 kW turbines were taken down after two years of weak production and little corporate interest.

On the other side of the country, in the deserted town of Altamont, California, two enthusiastic entrepreneurs pulled together massive funds to start putting up turbines in 1981. Over the ensuing four years, they would cover Altamont Pass with more than 1600 turbines. However, the pendulum of American politics never stops swinging. In 1986, the tax credits were repealed (along with many other energy subsidies) as part of President Ronald Reagan’s push to free up markets by reducing regulation and market-distorting subsidies. As we saw earlier, this is not strange. Indeed, the strange part was how involved in the market the federal government was becoming. Reagan was simply upholding traditional American values.

Building at Altamont stopped, and since then it has become the beloved child of anti-wind activists around the world. A report in 1992 found that on average 39 golden eagles were being killed every year and that two to four thousand other birds were being cut down every year. The pass is both a migration route and a favorable hunting ground for raptors, who are also attracted to the lattice towers perfect for nesting. Building did eventually resume, reaching nearly 5000 turbines at one point, but recent years have seen repowering efforts that are rapidly reducing the number of turbines while increasing capacity.

The wind rush of the early 1980s was important for the industry itself, but in terms of overall energy production, it was irrelevant. It didn’t even put wind energy in the energy mix. What did was the Energy Policy Act of 1992, which included the Production Tax Credit (PTC), a $0.023/kWh tax credit pegged to inflation that would boost wind energy (and other renewable energy) profits for the first 10 years of the project. The history of wind energy development in the US has been defined by the roller-coaster fate of the PTC.

The Production Tax Credit (PTC)

First of all, let’s clarify the PTC. It is not a direct subsidy. The government is not handing cash to developers or operators. It is a tax credit. That means that the company gets to take that amount of money off of their tax liability. However, if the company doesn’t have a tax liability, tax credits are useless. This results in a strange market where renewable energy companies “sell” tax credits to investors who have a much larger tax appetite. In this way, cutting corporate taxes (as happened in 2017) actually hurt the renewable industry because investors had a smaller tax appetite. But in terms of how the PTC affects the market, we can see it as a subsidy because it really is money that the government would have otherwise taken from the company.

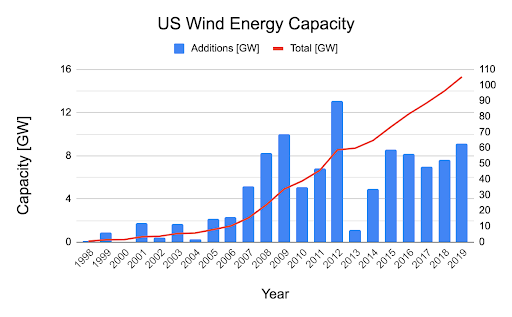

When we look at the rate of wind energy development, we see a repeating cycle of boom and bust. This occurs as developers rush to empty their development pipeline when an expiration of the PTC is approaching. This first happens at the first expiration at the end of 1999 (which was written into the original legislation). The PTC was extended at the end of 1999, but projects had already been fast-tracked, and development drops off in 2000 (also with a recession). The extension only goes through 2001, and development drops again in 2002. The same thing happens with the renewal in 2002 and expiration in 2003. After the drop in 2004, the industry sees five years of what looks to be exponential growth. Perhaps the industry was getting used to the expiration and renewal, so the sunset deadlines in 2005 and 2007 seem to have no impact on development rates. However, the PTC expiration at the end of 2009 in combination with the Great Recession limits development in 2010 and 2011. The 2009 extension goes through 2012 giving developers a bit of breathing room and development remains much higher than in the previous decade, reaching a crescendo at the end of 2012. There is an extension through 2013, but it comes on January 2nd of that year, which is basically meaningless to the industry that just emptied its pipelines to meet the deadline three days earlier.

Why the industry reacted so drastically to this expiration probably had to do with the political shift in Washington. The Republicans had regained control of the House of Representatives in 2010. The party has been consistently hostile to subsidies for just about anything except defense and law enforcement. Many were also notably loyal to the fossil fuel industry. With the risk of having a Republican Senate and White House, there was probably doubt that the PTC would be extended so quickly. In the end, the Democrats held both, and development climbed back to its 2007 level by 2015.

The extension in 2015 included a phase-out starting in 2017 that reduced the value each year by 20% until the end of 2019 when the PTC disappeared. In Trumpistan where wind is the cheapest form of new generation, we can expect that the PTC is permanently dead now.

Everything’s bigger in Texas

But how did the industry suddenly reach maturity in 2014? They continued building despite the fact that Washington was doing very little to help them. There are many reasons, but one is that they got a giant playground in which to hone their skills over the preceding five years. In 2008, then-Governor Rick Perry (yes, the same Rick Perry who proposed some garbage about making coal plants stockpile coal for energy security) pushed heavily for the expansion of transmission capacity throughout Texas.

Texas has the same problem as much of the Great Plains: millions of tens of thousands of miles of emptiness that are perfect for wind turbines but with nobody to use the electricity. Starting in 2008, Texas pushed for $7 billion of new transmission via the Public Utilities Commission (PUC), the state’s instrument for forcing the utilities to do things. As a result, Texas surged to the top of the list of wind energy producers, now having over three times the generating capacity of number two, Iowa and making up nearly 17% of their electricity and a quarter of US wind capacity. Despite all of this, wind development appears to have reached a plateau.

Now that wind is the cheapest form of new generation (post PTC PPAs are being signed below $20/MWh), why isn’t there another ‘wind rush’? There are several answers to that question, but I’ll address a few of them in the next section.

Current state of the industry

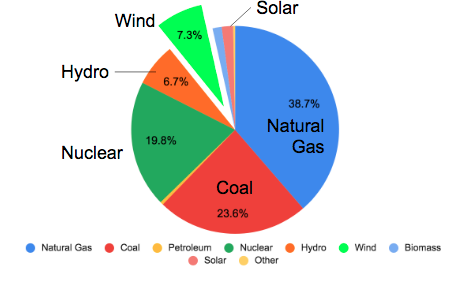

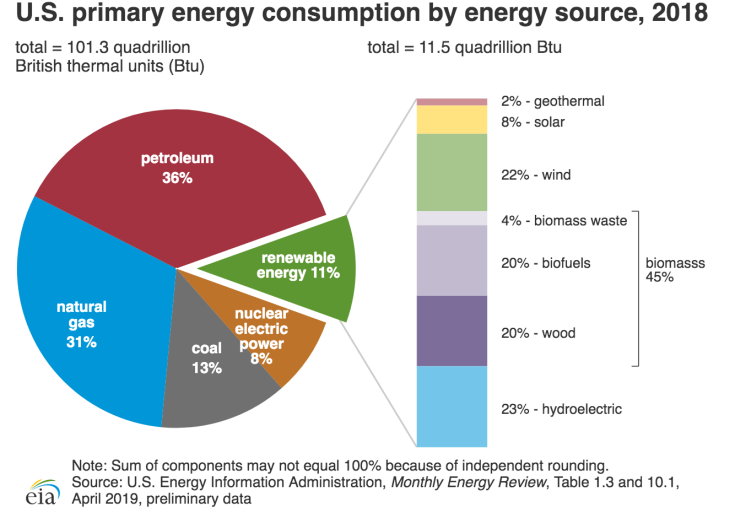

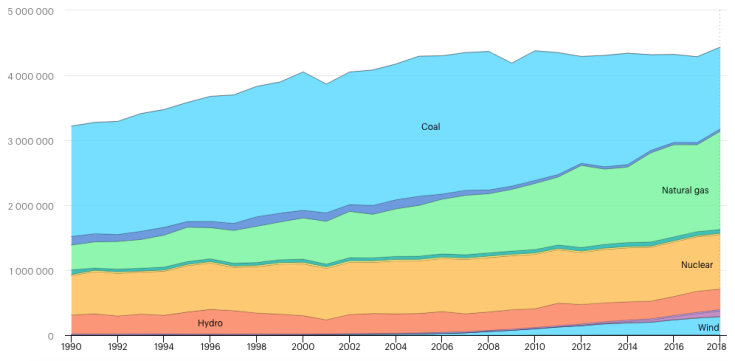

First of all, let’s look at where exactly we stand. As a share of electricity mix, wind has made great progress, recently displacing hydro as the largest renewable generator. However, it still pales in comparison to coal, natural gas, and even nuclear.

When we look at overall energy mix, the picture is even bleaker with wind not even getting its own slice of the pie but being lumped in with renewables.

Even though the US is the largest producer of wind energy in the world (second in capacity), it barely makes a dent in our energy usage. The scale of wind energy needed to power our country is indeed a challenge, but it’s also the largest economy in the world with one of the largest work forces. There should be plenty of capital (financial and human) to build wind farms like we build cookie-cutter suburban houses.

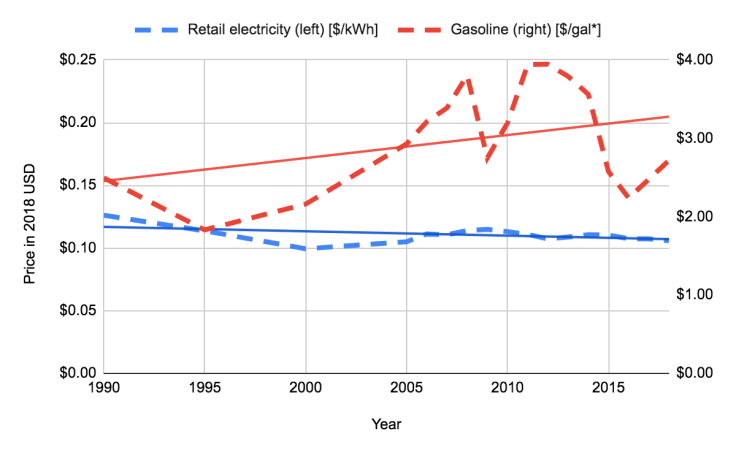

To me, the most salient reason for the comparatively slow development of wind energy is the lack of financial incentive. Yes, new wind energy has a very low levelized cost of energy (LCOE), but even if it were free, there’s just not much room to make energy cheaper. I continually joke with my friends and my family that energy is free in this country. At least at this rate, it will be soon.

This is a figure of electricity prices and gasoline prices in the US over the past three decades, adjusted for inflation. Electricity just keeps getting cheaper, so the goal post of decreasing renewable costs keeps moving further away. I’ve added gasoline prices because most American personal vehicles run on gasoline. We don’t tax cars at nearly the same rate as European countries, and with fuel prices so cheap, there is no financial incentive to buy an EV (despite many state and federal tax breaks), meaning that oil will continue to make up a huge chunk of our energy supply. With energy prices one half, one third or even less compared to prices in Europe, there’s little financial incentive to invest in something new, i.e. renewables.

Part of what keeps these energy prices low is natural gas. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a few new technological advances (spurred by deregulation that removed the requirement of companies to disclose what’s in their fracking fluid) greatly increased the amount of recoverable natural gas. Since the fracking boom around 2010, gas extraction has been rising exponentially, making the US the largest producer (and consumer) of natural gas, surging ahead of Russia in 2013. Natural gas power plants continues to make up a large share of new capacity additions each year. When we look at the decline of coal, we can blame fracking, not renewables. New fossil fuels mean a bigger resistance because of the fear of stranded assets.

It’s all really a matter of supply and demand. Every energy company has a development department that is pushing for adding new capacity, but electricity demand in the country has been basically flat for years (partly due to lack of electrification because of cheap oil and natural gas). With flat demand, wind and solar can grow only as fast as coal dies, and that will make solar our new worst enemy in the wind industry.

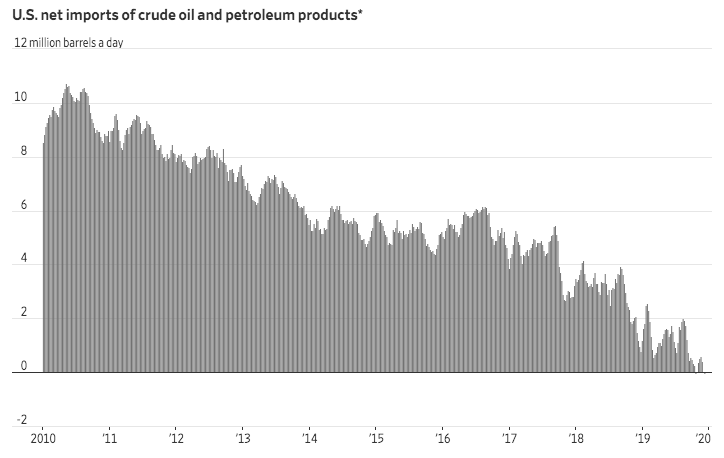

There’s also the cultural resistance. The America that prides itself on self-reliance has only been bolstered by the realization of energy independence this year.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-decade-in-which-fracking-rocked-the-oil-world-11576630807

Fracking also helps us get at oil. We still import a great deal of oil, but we export just as much. If international shipping got cut off, we could literally run our entire economy on coal, oil, and natural gas extracted from beneath the United States. The argument that wind energy provides for energy security doesn’t have much traction. An intermittent source, dependent on the weather, and seemingly unproven for many people seems like the opposite of “reliable”.

When cities and towns have been built on coal and oil, it’s hard to convince them to leave their ancestry behind. When oil and gas are still paying the bills today, it’s impossible. The US fossil fuel industry funded over 10 million jobs in 2015 (perhaps less now, but those who have lost those jobs probably aren’t working for renewables now). Compare that to about half a million renewable jobs in 2019. The average salary in the fossil fuel industry was over $100 thousand, almost double the national median. The median salary of a renewable energy technician is about $56 thousand. Not to mention the fact that renewable technician jobs are not steady. Either they’re installation and construction jobs that move when the project is finished, or they’re maintenance technicians who service a wide area. Going to the same extraction site every day is much simpler for many people.

Finally, we’re simply running out of space. I don’t necessarily mean physical space (although many of the best spots have been taken), but I mean space on the wires. Building new power plants means building new transmission lines. When I worked as a developer, we seriously considered building 150-mile-long transmission lines just to find a good place to connect to the grid. For an energy developer to do such a thing 10 years ago was insanity. Nobody wants that thankless task. It’s a tough way to make money, and it requires enormous capital investments. One estimate puts the cost of a new 500 kV double circuit line at $300 million per mile. The power line will end up costing ten to a hundred times what it costs to build the wind farm!

Remember who owns land in the US. Federal land is expensive, and it takes time to get permitted. Private land is expensive because of course it is! You want to put what on my property?! Fine, but you’ll pay for it!

However, with all of these factors working against renewables, they continue to grow. When talk about climate change started to pick up and the economics of wind energy started to make more sense in the early 2010s, there was a surge of corporate leadership. Especially since the election of Trump (who claimed that climate change was a hoax), more and more corporate leaders have gotten onboard. Launched in 2014, the RE100 is a list of companies committed to 100% renewables between 2020 and 2050. When I reported on this in 2017, there were 111 companies on the list. It has since doubled. Corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) continue to fund about half of new wind projects. A VP of Google one said, “We are technology agnostic; we are not price agnostic.”

My bet will be that new capacity growth of wind has basically plateaued. With the PTC fading out at the end of last year, I would expect that 2020 will have slightly less installation but the coming years will average out at about the same 50-60 GW/year.

The future of the industry

Here are a few things I expect to happen in the coming decade.

Offshore is going to grow, but not as quickly as industry analysts hope. There is a lot of interest, especially in the US East Coast, but offshore is harder than people think. First of all, we need to understand that the North and Baltic Seas were basically made for offshore wind power. A nearly infinite expanse of 20-40 m deep water that doesn’t get hurricanes. The US doesn’t have much of that. There’s a reason why we only have one offshore wind farm (developed by DONG/Orsted). The continental shelf around most of the US is very slim, meaning that most potential sites are at a depth of 40 m, 60 m, or deeper. That means that floating is going to be the only option for many states. It’s true that there are now commercial projects like Hywind off Scotland and Windfloat off Portugal, but they’re still going to be far more expensive than bottom-fixed in the near future, and even those will be too expensive. Remember that wholesale electricity in the US is dirt cheap, and onshore wind in going for less than $20/MWh. Even optimistic analysis has offshore leveling out at an LCOE of $40-50/MWh. Part of that cost is long permitting times. In California, they need 33 permits to build offshore. Compare that to many places in the interior that need maybe two or three. That kind of development time and high cost just won’t cut it in this market.

However, there are some big industry names developing wind farms off the US East Coast. Orsted, Equinor, and Avangrid all have plans. They will surely follow through on some, but it’s not going to be another wind rush.

Renewables will continue to grow, but wind is going to get overshadowed by solar. Much analysis is showing more growth of solar and better returns for investment in PV. Wind PPAs have leveled off at an average about $26/MWh while solar is still falling through $27/MWh. Part of that is transmission. It’s much easier to build a solar farm right on top of an existing substation; solar resource doesn’t change much with local orography. Most utility companies don’t have the incentive to spend billions on running wires out to the middle of nowhere.

However, there are people trying to do it. Wyoming is a state with the population of Iceland but more than double its size where the wind never stops blowing. There are two projects trying to export that wind resource to the West Coast, but they’ve been in the works for over a decade (TransWest Express, Gateway West). And they may well end up getting canceled like a similar big project to send wind from western Kansas to Indiana (Grainbelt Express). In all likelihood, utilities will continue with plans to rebuild and upgrade current infrastructure on land they already have access to. That benefits solar, not wind.

One consideration that will become a larger factor as variable renewables make up more of the electricity mix is stability and reliability. That’s going to mean that more projects will be hybrid, combining two or more of wind, solar and storage at the same interconnection point. Solar + storage is standard for developers like Invenergy, but wind + storage hasn’t caught on yet. I only found one project in the works so far.

The future of the wind industry isn’t grim, but it’s not exactly blooming either. However, there is one thing that could change that: policy. In Trumpistan, new policies that would benefit renewables seem highly unlikely, but there are enough rumblings that could make 2025 a very momentous year when the Republicans lose the White House (just guessing here, but that seems to be the trend).

I’m not talking about a Green New Deal. A country so fearful of socialism would never go for such a draconian and delusional policy framework. I’m talking about a carbon tax, the most conservative approach to tackling climate change that there is. It’s technology agnostic, corrects for current externalities, and compliant with free-market principles. At least eight carbon pricing bills were introduced in the 116th Congress (the one that started January 2018). It’s not partisan; most of the bills are either bipartisan or introduced by Republicans. The Climate Leadership Council, a think tank founded by conservative leaders who are pushing for a carbon tax, has exceptionally deep pockets and firm support from the fossil fuel industry. Again, I doubt this will happen in the next four years, but as soon as Trump is out of the way, there will likely be something ready for the next president to sign.

Conclusion

I’ve left out great deal of information here, but I hope I highlighted some things that were useful and interesting. Most of all, I hope that I have pointed out some of the ways in which cultural differences can lead to very different approaches to solving the same problem. There are thousands of Americans working tirelessly to combat climate change, despite what you may hear on the news and from the government. How they do that work, though, is different from how it is done in Europe.

We may refer to government officials as “leaders”, but we all know that’s not true. They are representatives of the people. They do our bidding (or at least they’re supposed to). In the US, the President does not have the power and Congress would never have the consensus to enforce such measures as an “Energiewende”. Politicians can set goals, but they’re just numbers on paper. Americans do not simply accept the authority of the government. The right to govern depends on the consent of the governed in this country.

I fully expect that wind energy will continue to expand, and anyone working in the industry is in a good place. However, claims of a coming exponential growth of renewables are unfounded. I could argue all day as to why that is, but I don’t need to. The numbers are in, and the period of exponential growth has ceased for wind energy in America.

… unless there’s a carbon tax. That would change everything.